Post by Mad Scientist on Aug 18, 2018 18:48:09 GMT

Two Pilots Saw a UFO. Why Did the Air Force Destroy the Report?

Whatever occurred at 2:45 a.m. on the morning of July 24, 1948 in the skies over southwest Alabama not only shocked and stymied the witnesses. It jolted the U.S. government into a top-secret investigation—the results of which were ultimately destroyed.

The skies were mostly clear and the moon was bright in the pre-dawn hours as pilot Clarence S. Chiles and co-pilot John B. Whitted flew their Eastern Air Lines DC-3, a twin-engine propeller plane, at 5,000 feet, en route from Houston to Atlanta. The aircraft had 20 passengers on board, 19 of them asleep at that hour. It was a routine domestic flight, one of many in the skies that early morning.

Until suddenly, it wasn’t. What the two pilots and their wide-awake passenger saw in the skies about 20 miles southwest of Montgomery, Alabama, did more than startle them. It would reportedly become the catalyst for a highly classified Air Force document suggesting that some unidentified flying objects were spaceships from other worlds—a tipping point in UFO history.

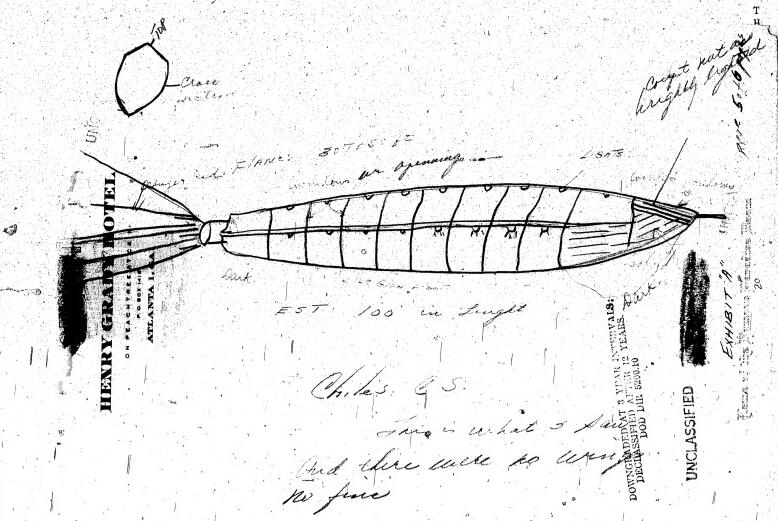

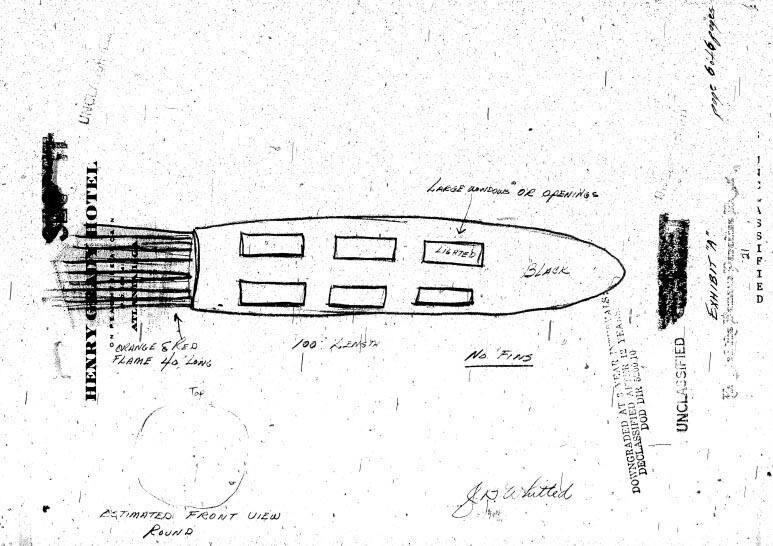

Chiles described what he saw in an official statement about a week later: “It was clear there were no wings present, that it was powered by some jet or other type of power, shooting flame from the rear some 50 feet. There were two rows of windows, which indicated an upper and lower deck, [and] from inside these windows a very bright light was glowing. Underneath the ship there was a blue glow of light.” He estimated that he’d watched the ship for about 10 seconds before it disappeared into some light clouds and was lost from view.

Whitted offered a similar description in his official statement: “The object was cigar shaped and seemed to be about a hundred feet in length. The fuselage appeared to be about three times the circumference of a B-29 fuselage. It had two rows of windows, an upper and a lower. The windows were very large and seemed square. They were white with light which seemed to be caused by some type of combustion…. I asked Capt. Chiles what we had just seen and he said that he didn’t know.”

The passenger who was awake at the time, Clarence L. McKelvie of Columbus, Ohio, corroborated the pilots’ account that an unusually bright object had streaked past his window, but he wasn’t able to describe it beyond that.

Both pilots also made drawings of the craft they believed they had seen and provided further details in newspaper and radio interviews, some just hours after the sighting. The Atlanta Constitution headlined its July 25 account, “Atlanta Pilots Report Wingless Sky Monster.” In that article, Chiles described what sounded like an uncomfortably close encounter, as the object appeared to be coming at them. “We veered to the left and it veered to its left, and passed us about 700 feet to our right and about 700 feet above us. Then, as if the pilot had seen us and wanted to avoid us, it pulled up with a tremendous burst of flame out of its rear and zoomed up into the clouds.”

Chiles and Whitted weren’t the only ones baffled by what they’d seen.

Asked for comment, William M. Allen, the president of Boeing Aircraft told the United Press he was “pretty sure” it was “not one of our planes,” adding that he knew of nothing being built in the U.S. that matched the description. General George C. Kenney, the chief of the Strategic Air Command, which was responsible for most of America’s nuclear strike forces during the Cold War, told the Associated Press: “The Army hasn’t anything like that. I wish we did.”

Whatever Chiles and Whitted witnessed, theirs was far from an isolated incident. There had been scores of reported UFO sightings in the years just previous. But Air Force investigators took this one more seriously than most. For one thing, both men were highly regarded pilots who had served as Air Force officers during World War II. (McKelvie was also a solid citizen and an Air Force veteran, as well.) For another, the pilots had gotten what seemed to be an unusually close look at the strange object they described.

For all of those reasons, the Chiles-Whitted encounter, as it came to be known, reportedly caused the Air Technical Intelligence Center to draft a top-secret document with the deceptively bland title “Estimate of the Situation.” Edward J. Ruppelt, an Air Force officer and the first head of its famous Project Blue Book study of UFO phenomena, claimed to have seen a copy. “The ‘situation’ was the UFOs,” he wrote, “the ‘estimate’ was that they were interplanetary!”

According to Ruppelt, the report traveled up the Air Force chain of command all the way to General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, the chief of staff. “The general wouldn’t buy interplanetary vehicles,” Ruppelt wrote. “A group from ATIC went to the Pentagon to bolster their position but had no luck, the Chief of Staff couldn’t be convinced.”

Ruppelt continued, “The estimate died a quick death. Some months later it was completely declassified and relegated to the incinerator.”

One reason for Vandenberg’s skepticism, apparently, was that another faction within the Air Force had a competing theory: UFOs weren’t interplanetary at all, but the handiwork of America’s Cold War nemesis, the Soviet Union. In another top-secret report dated December 1948, the Air Force suggested a variety of reasons the Soviets might be behind such a scheme, including photographic reconnaissance, testing U.S. air defenses and undermining U.S. and European ally confidence in the atom bomb as the ultimate weapon. The Soviets wouldn’t have their own atom bomb until late August 1949.

The suppression of the “Estimate of the Situation” and the rejection of any extraterrestrial explanation was the start of “a long period of unfortunate, amateurish public relations” on the part of the Air Force, astronomer J. Allen Hynek claimed in his 1972 book, The UFO Experience. Hynek, who had worked at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory tracking space satellites and later became a professor at Northwestern University, was the official astronomical consultant to Project Blue Book as well as the man who developed the UFO-sighting classification system that originated the phrase “Close Encounters of Third Kind.”

“The insistence on official secrecy and frequent ‘classification’ of documents was hardly needed since the Pentagon had declared that the problem really didn’t exist,” Hynek wrote.

Ruppelt maintained that bureaucratic bungling rather than deliberate deception was the Air Force’s main problem. “But had the Air Force tried to throw up a screen of confusion, they couldn’t have done a better job,” he added.

In part because of this lack of transparency, the Chiles-Whitted incident remains one of the most controversial UFO sightings—and a favorite of conspiracy theorists even now.

So, what did Chiles and Whitted actually see? Some suggested a weather balloon, others a mirage. Hynek believed it was a fireball, or very bright meteor, an opinion that eventually became the official Air Force verdict. As to the lighted windows both pilots claim to have seen, some experts suggest that might have been a phenomenon called the “airship effect,” where observers who see a group of unrelated lights in the sky are fooled into thinking they’re part of the same object.

But Chiles and Whitted stuck to their story. James E. McDonald, a University of Arizona physicist and UFO expert, said he interviewed them in 1968, some 20 years after the event. The two were now jet pilots for Eastern Air Lines, and they continued to believe that what they had seen was some sort of airborne vehicle, McDonald reported.

What’s more, Whitted added a new and puzzling detail to the story. Although reports at the time said the object had disappeared into the clouds or simply out of their view, he supposedly told McDonald that wasn’t what really happened. Instead, the object had vanished instantaneously, right before their eyes.

No wonder the Chiles-Whitted case continues to baffle and intrigue, even 70 years later.

Source

Whatever occurred at 2:45 a.m. on the morning of July 24, 1948 in the skies over southwest Alabama not only shocked and stymied the witnesses. It jolted the U.S. government into a top-secret investigation—the results of which were ultimately destroyed.

The skies were mostly clear and the moon was bright in the pre-dawn hours as pilot Clarence S. Chiles and co-pilot John B. Whitted flew their Eastern Air Lines DC-3, a twin-engine propeller plane, at 5,000 feet, en route from Houston to Atlanta. The aircraft had 20 passengers on board, 19 of them asleep at that hour. It was a routine domestic flight, one of many in the skies that early morning.

Until suddenly, it wasn’t. What the two pilots and their wide-awake passenger saw in the skies about 20 miles southwest of Montgomery, Alabama, did more than startle them. It would reportedly become the catalyst for a highly classified Air Force document suggesting that some unidentified flying objects were spaceships from other worlds—a tipping point in UFO history.

Chiles described what he saw in an official statement about a week later: “It was clear there were no wings present, that it was powered by some jet or other type of power, shooting flame from the rear some 50 feet. There were two rows of windows, which indicated an upper and lower deck, [and] from inside these windows a very bright light was glowing. Underneath the ship there was a blue glow of light.” He estimated that he’d watched the ship for about 10 seconds before it disappeared into some light clouds and was lost from view.

Whitted offered a similar description in his official statement: “The object was cigar shaped and seemed to be about a hundred feet in length. The fuselage appeared to be about three times the circumference of a B-29 fuselage. It had two rows of windows, an upper and a lower. The windows were very large and seemed square. They were white with light which seemed to be caused by some type of combustion…. I asked Capt. Chiles what we had just seen and he said that he didn’t know.”

The passenger who was awake at the time, Clarence L. McKelvie of Columbus, Ohio, corroborated the pilots’ account that an unusually bright object had streaked past his window, but he wasn’t able to describe it beyond that.

Both pilots also made drawings of the craft they believed they had seen and provided further details in newspaper and radio interviews, some just hours after the sighting. The Atlanta Constitution headlined its July 25 account, “Atlanta Pilots Report Wingless Sky Monster.” In that article, Chiles described what sounded like an uncomfortably close encounter, as the object appeared to be coming at them. “We veered to the left and it veered to its left, and passed us about 700 feet to our right and about 700 feet above us. Then, as if the pilot had seen us and wanted to avoid us, it pulled up with a tremendous burst of flame out of its rear and zoomed up into the clouds.”

Chiles and Whitted weren’t the only ones baffled by what they’d seen.

Asked for comment, William M. Allen, the president of Boeing Aircraft told the United Press he was “pretty sure” it was “not one of our planes,” adding that he knew of nothing being built in the U.S. that matched the description. General George C. Kenney, the chief of the Strategic Air Command, which was responsible for most of America’s nuclear strike forces during the Cold War, told the Associated Press: “The Army hasn’t anything like that. I wish we did.”

Whatever Chiles and Whitted witnessed, theirs was far from an isolated incident. There had been scores of reported UFO sightings in the years just previous. But Air Force investigators took this one more seriously than most. For one thing, both men were highly regarded pilots who had served as Air Force officers during World War II. (McKelvie was also a solid citizen and an Air Force veteran, as well.) For another, the pilots had gotten what seemed to be an unusually close look at the strange object they described.

For all of those reasons, the Chiles-Whitted encounter, as it came to be known, reportedly caused the Air Technical Intelligence Center to draft a top-secret document with the deceptively bland title “Estimate of the Situation.” Edward J. Ruppelt, an Air Force officer and the first head of its famous Project Blue Book study of UFO phenomena, claimed to have seen a copy. “The ‘situation’ was the UFOs,” he wrote, “the ‘estimate’ was that they were interplanetary!”

According to Ruppelt, the report traveled up the Air Force chain of command all the way to General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, the chief of staff. “The general wouldn’t buy interplanetary vehicles,” Ruppelt wrote. “A group from ATIC went to the Pentagon to bolster their position but had no luck, the Chief of Staff couldn’t be convinced.”

Ruppelt continued, “The estimate died a quick death. Some months later it was completely declassified and relegated to the incinerator.”

One reason for Vandenberg’s skepticism, apparently, was that another faction within the Air Force had a competing theory: UFOs weren’t interplanetary at all, but the handiwork of America’s Cold War nemesis, the Soviet Union. In another top-secret report dated December 1948, the Air Force suggested a variety of reasons the Soviets might be behind such a scheme, including photographic reconnaissance, testing U.S. air defenses and undermining U.S. and European ally confidence in the atom bomb as the ultimate weapon. The Soviets wouldn’t have their own atom bomb until late August 1949.

The suppression of the “Estimate of the Situation” and the rejection of any extraterrestrial explanation was the start of “a long period of unfortunate, amateurish public relations” on the part of the Air Force, astronomer J. Allen Hynek claimed in his 1972 book, The UFO Experience. Hynek, who had worked at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory tracking space satellites and later became a professor at Northwestern University, was the official astronomical consultant to Project Blue Book as well as the man who developed the UFO-sighting classification system that originated the phrase “Close Encounters of Third Kind.”

“The insistence on official secrecy and frequent ‘classification’ of documents was hardly needed since the Pentagon had declared that the problem really didn’t exist,” Hynek wrote.

Ruppelt maintained that bureaucratic bungling rather than deliberate deception was the Air Force’s main problem. “But had the Air Force tried to throw up a screen of confusion, they couldn’t have done a better job,” he added.

In part because of this lack of transparency, the Chiles-Whitted incident remains one of the most controversial UFO sightings—and a favorite of conspiracy theorists even now.

So, what did Chiles and Whitted actually see? Some suggested a weather balloon, others a mirage. Hynek believed it was a fireball, or very bright meteor, an opinion that eventually became the official Air Force verdict. As to the lighted windows both pilots claim to have seen, some experts suggest that might have been a phenomenon called the “airship effect,” where observers who see a group of unrelated lights in the sky are fooled into thinking they’re part of the same object.

But Chiles and Whitted stuck to their story. James E. McDonald, a University of Arizona physicist and UFO expert, said he interviewed them in 1968, some 20 years after the event. The two were now jet pilots for Eastern Air Lines, and they continued to believe that what they had seen was some sort of airborne vehicle, McDonald reported.

What’s more, Whitted added a new and puzzling detail to the story. Although reports at the time said the object had disappeared into the clouds or simply out of their view, he supposedly told McDonald that wasn’t what really happened. Instead, the object had vanished instantaneously, right before their eyes.

No wonder the Chiles-Whitted case continues to baffle and intrigue, even 70 years later.

Source